I’m an Episcopalian. It means a lot to me to have this religious affiliation, but I mostly keep it to myself as a deeply private belief. One of the things I love most about the Episcopal church is the repetition of the liturgy from week to week. Before I became an Episcopalian I used to think that I would find the repetition incredibly boring, but the truth is, it’s very comforting. No matter what is going on in the world, there is a lovely set of words to return to, week after week, day after day, that don’t change. Words that provide comfort, assurance, even easing tensions and pains from daily living.

Alexander’s directions,“Let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, to let the back lengthen and widen,to let the knees go forward and away” can have the same effect on me as the liturgy. Because I have had much experience from the hands of Alexander teachers, all I have to do is think these words and I experience comfort, an easing of physical tension, and I sense my place in the physical world. These words bring me home to myself.

As a beginner to the technique, without a lot of experience, these words meant nothing to me. As a teacher, I often hear beginning students ask me “But how do I free my neck?”

In recent years, people have made some adaptations of Alexander's directions to be easier to understand and more accessible without a teacher. I think this is all good. I’m thankful that innovative directions exist and that people are continuing to explore new and effective ways to communicate our work.

Alexander’s directions,“Let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, to let the back lengthen and widen,to let the knees go forward and away” can have the same effect on me as the liturgy. Because I have had much experience from the hands of Alexander teachers, all I have to do is think these words and I experience comfort, an easing of physical tension, and I sense my place in the physical world. These words bring me home to myself.

As a beginner to the technique, without a lot of experience, these words meant nothing to me. As a teacher, I often hear beginning students ask me “But how do I free my neck?”

In recent years, people have made some adaptations of Alexander's directions to be easier to understand and more accessible without a teacher. I think this is all good. I’m thankful that innovative directions exist and that people are continuing to explore new and effective ways to communicate our work.

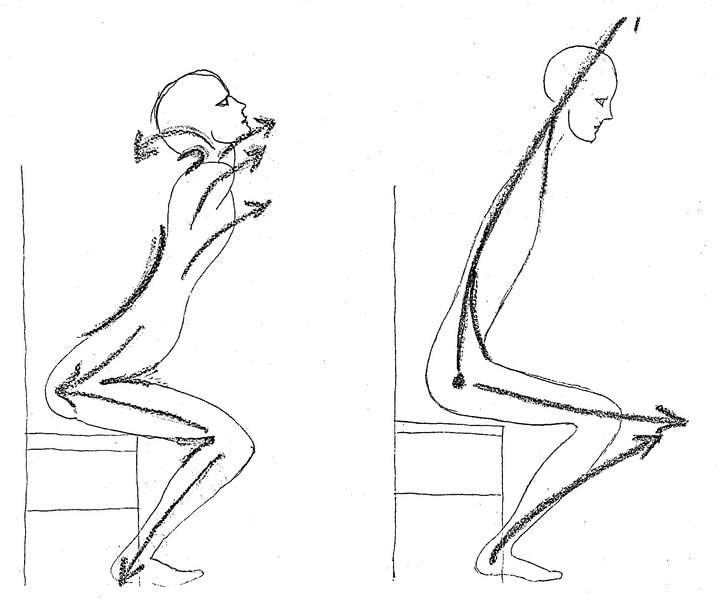

Two ways to get out of a chair:

On the left, with the head tipped backwards and pulled down, the direction of motion is towards the floor. No wonder it's so hard to get up!

On the right, the person is directing themselves forward and up out of the chair. You can learn how to do this in an Alexander lesson.

On the left, with the head tipped backwards and pulled down, the direction of motion is towards the floor. No wonder it's so hard to get up!

On the right, the person is directing themselves forward and up out of the chair. You can learn how to do this in an Alexander lesson.

An early adaptation of directions came from Missy Vineyard in her 1997 book “How You Stand, How You Move, How You Live.” Missy came up with the idea of negative directions. Instead of saying “let your neck be free,” the corresponding negative direction would be something like “my neck is not tense.” Negative directions work, but the very inference of the word “negative” is something I really don’t enjoy bringing to my work. I have to say that I have seldom used these in my teaching.

My colleague and friend Jennifer Roig-Francoli, who is a wonderful boundary explorer in the AT world, has created “Freedom Directions.” Instead of all of Alexander’s words, the Freedom Directions simply say this:

· My neck is free

· I am free

· My breathing is free

· My legs are free

When I use the Freedom Directions, I notice that they give me a lot of space for interpretation of the given moment. In my own teaching, I like to remind students that “directions” can also refer to mental letting go, as well as physical letting go. Often, one informs the other – but using something as simply as “I am free” allows me to let go of whatever is NOT free in my body or my mind.

If the differences between these types of directions intrigues you, there are even more variations out there. You can find links to different kinds of directions on Robert Rickover’s website, Up With Gravity.

In my teaching, I like to use directions that help students to find the ground as well as finding the way “up.” I rather enjoy asking people to direct themselves from their center of gravity, allowing Up to pass through the crown of the head at the same time as allowing Down to go down into the floor. I find this particular helpful for actors, who need to have all of themselves on the stage.

I also like to tell students that directions are what we ask ourselves to do instead – and this asking comes through thinking, not through physical pushing or doing. This kind of directing can be done with virtually anything – a mental task, or a physical one.

Mental directing of what we would like to change in our physicality is an essential part of the Alexander Technique. In any given situation, how we direct and what we direct are up to us.

My colleague and friend Jennifer Roig-Francoli, who is a wonderful boundary explorer in the AT world, has created “Freedom Directions.” Instead of all of Alexander’s words, the Freedom Directions simply say this:

· My neck is free

· I am free

· My breathing is free

· My legs are free

When I use the Freedom Directions, I notice that they give me a lot of space for interpretation of the given moment. In my own teaching, I like to remind students that “directions” can also refer to mental letting go, as well as physical letting go. Often, one informs the other – but using something as simply as “I am free” allows me to let go of whatever is NOT free in my body or my mind.

If the differences between these types of directions intrigues you, there are even more variations out there. You can find links to different kinds of directions on Robert Rickover’s website, Up With Gravity.

In my teaching, I like to use directions that help students to find the ground as well as finding the way “up.” I rather enjoy asking people to direct themselves from their center of gravity, allowing Up to pass through the crown of the head at the same time as allowing Down to go down into the floor. I find this particular helpful for actors, who need to have all of themselves on the stage.

I also like to tell students that directions are what we ask ourselves to do instead – and this asking comes through thinking, not through physical pushing or doing. This kind of directing can be done with virtually anything – a mental task, or a physical one.

Mental directing of what we would like to change in our physicality is an essential part of the Alexander Technique. In any given situation, how we direct and what we direct are up to us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed